A Case Study on the Khurda Uprising

Much before the event of 1857, there had taken place another event of a similar nature at a place called Khurda in 1817. Here, it would be instructive for us to study that event and reflect on how resentment against the colonial policies of the British had been building up since the beginning of the 19th century in different parts of the country.

Khurda, a small kingdom built up in the late 16th century in the south-eastern part of Odisha, was a populous and well-cultivated territory consisting of 105 garhs, 60 large and 1109 small villages at the beginning of the 19th century. Its king, Raja Birakishore Dev had to earlier give up the possession of four parganas, the superintendence of the Jagannath Temple and the administration of fourteen garjats (Princely States) to the Marathas under compulsion. His son and successor, Mukunda Dev II was greatly disturbed with this loss of fortune. Therefore, sensing an opportunity in the Anglo-Maratha conflict, he had entered into negotiations with the British to get back his lost territories and the rights over the Jagannath Temple. But after the occupation of Odisha in 1803, the British showed no inclination to oblige him on either score. Consequently, in alliance with other feudatory chiefs of Odisha and secret support of the Marathas, he tried to assert his rights by force. This led to his deposition and annexation of his territories by the British. As a matter of consolation, he was only given the rights of management of the Jagannath Temple with a grant amounting to a mere one-tenth of the revenue of his former estate and his residence was fixed at Puri. This unfair settlement commenced an era of oppressive foreign rule in Odisha, which paved the way for a serious armed uprising in 1817.

Soon after taking over Khurda, the British followed a policy of resuming service tenures. It bitterly affected the lives of the ex-militia of the state, the Paiks. The severity of the measure was compounded on account of an unreasonable increase in the demand of revenue and also the oppressive ways of its collection. Consequently, there was large scale desertion of people from Khurda between 1805 and 1817. Yet, the British went for a series of shortterm settlements, each time increasing the demands, not recognising either the productive capacity of the land or the paying capacity of the ryots. No leniency was shown even in case of natural calamities, which Odisha was frequently prone to. Rather, lands of defaulters were sold off to scheming revenue officials or speculators from Bengal.

The hereditary Military Commander of the deposed king, Jagabandhu Bidyadhar Mahapatra Bhramarabar Rai or Buxi Jagabandhu as he was popularly known, was one among the dispossessed land-holders. He had in effect become a beggar, and for nearly two years survived on voluntary contributions from the people of Khurda before deciding to fight for their grievances as well as his own. Over the years, what had added to these grievances were (a) the introduction of sicca rupee (silver currency) in the region, (b) the insistence on payment of revenue in the new currency, (c) an unprecedented rise in the prices of food-stuff and salt, which had become far-fetched following the introduction of salt monopoly because of which the traditional salt makers of Odisha were deprived of making salt, and (d) the auction of local estates in Calcutta, which brought in absentee lan dlords from Bengal to Odisha. Besides, the insensitive and corrupt police system also made the situation worse for the armed uprising to take a sinister shape.

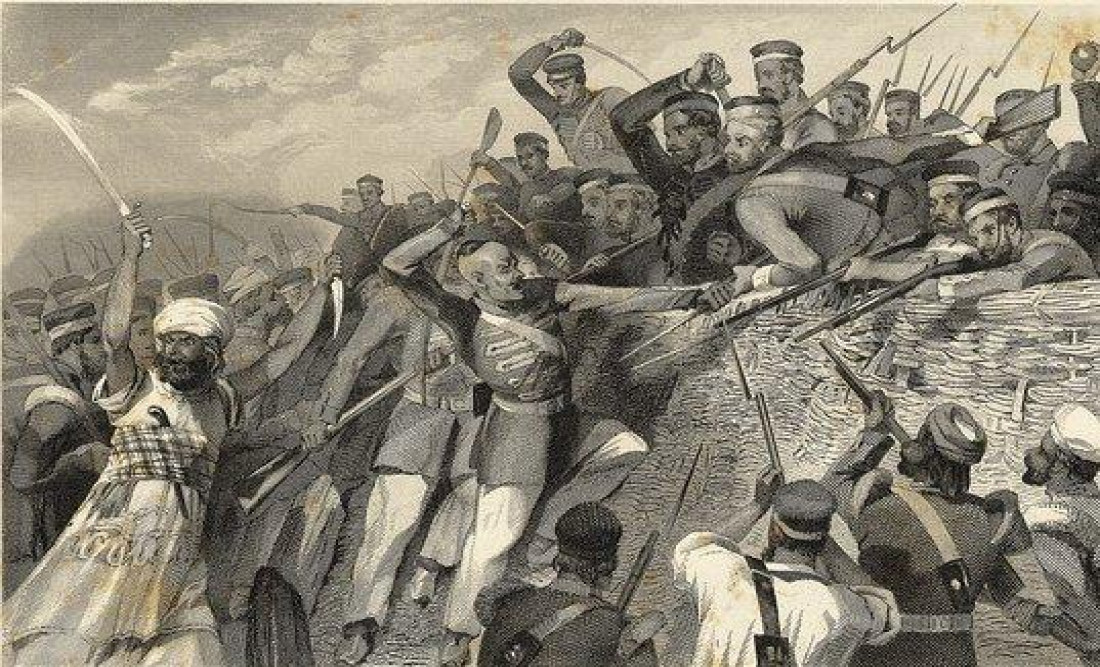

The uprising was set off on 29 March 1817 as the Paiks attacked the police station and other government establishments at Banpur killing more than a hundred men and took away a large amount of government money. Soon its ripples spread in different directions with Khurda becoming its epicenter. The zamindars and ryots alike joined the Paiks with enthusiasm. Those who did not, were taken to task. A ‘no-rent campaign’ was also started. The British tried to dislodge the Paiks from their entrenched position but failed. On 14 April 1817, Buxi Jagabandhu, leading five to ten thousand Paiks and men of the Kandh tribe seized Puri and declared the hesitant king, Mukunda Dev II as their ruler. The priests of the Jagannath Temple also extended the Paiks their full support.

Seeing the situation going out of hand, the British clamped Martial Law. The King was quickly captured and sent to prison in Cuttack with his son. The Buxi with his close associate, Krushna Chandra Bhramarabar Rai, tried to cut off all communications between Cuttack and Khurda as the uprising spread to the southern and the north-western parts of Odisha. Consequently, the British sent Major-General Martindell to clear off the area from the clutches of the Paiks while at the same time announcing rewards for the arrest of Buxi jagabandhu and his associates. In the ensuing operation hundreds of Paiks were killed, many fled to deep jungles and some returned home under a scheme of amnesty. Thus by May 1817 the uprising was mostly contained.

However, outside Khurda it was sustained by Buxi Jagabandhu with the help of supporters like the Raja of Kujung and the unflinching loyalty of the Paiks until his surrender in May 1825. On their part, the British henceforth adopted a policy of ‘leniency, indulgence and forbearance’ towards the people of Khurda. The price of salt was reduced and necessary reforms were made in the police and the justice systems. Revenue officials found to be corrupt were dismissed from service and former land-holders were restored to their lands. The son of the king of Khurda, Ram Chandra Dev III was allowed to move to Puri and take charge of the affairs of the Jagannath Temple with a grant of rupees twenty-four thousand.

In sum, it was the first such popular anti-British armed uprising in Odisha, which had far reaching effect on the future of British administration in that part of the country. To merely call it a ‘Paik Rebellion’ will thus be an understatement.

Manoj Bhiva

Manoj Bhiva is a dedicated writer who loves to write on any subject. Manoj Bhiva maintains a similar hold on politics, entertainment, health, abroad articles. Manoj Bhiva has total experience of 3 years in web and Social. Manoj Bhiva works as a writer in Wordict Post.

Russian Rocket 'Totally Destroys' Dorm, Unknown Amount Dead: Zelensky

Posted on 18th Aug 2022